Whether you’re a teacher or a student, you know from experience that lessons with more dynamic, visual elements are more likely to stick in your mind. Research shows that we learn better when our materials include a mixture of both graphics and text, and that’s where multimedia instruction comes in.

Table of Contents

What Is Multimedia Instruction?

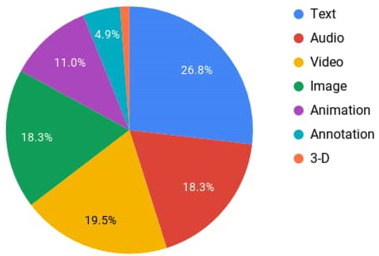

Multimedia instruction is simply a lesson containing both words and pictures. The words can be either read or spoken aloud. The pictures can be moving images like video or animation, or stationary. The vast majority of contemporary classrooms incorporate multimedia learning.

Multimedia instruction can refer to e-learning tools, video lessons, or PowerPoint presentations. If you teach online, maybe you use a cloud-based phone service for video calls and screen sharing. However, multimedia instruction can also simply mean learning from an illustrated book.

The key to good multimedia instruction is that the visual elements complement the text and allow for a greater understanding of the lesson’s content.

Why Use Multimedia Instruction?

Let’s take a look at the scientific basis for the multimedia style of teaching and learning.

Short-term and long-term memory

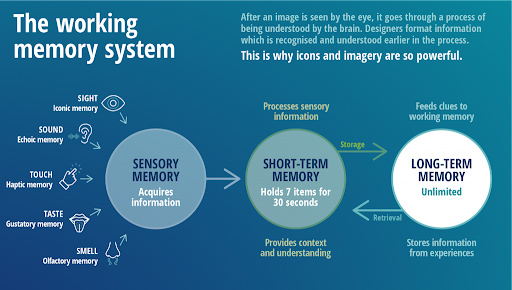

You may already know that you have two kinds of memory.

Your short-term memory retains information for a brief period of time. Its capacity is limited: generally, we can only remember about seven pieces of new information at once, plus or minus two.

Most information is only stored for 20–30 seconds, with a minute as an absolute maximum, unless you employ a strategy to keep the memory fresh, such as repeating the information out loud.

Distraction can also cause you to forget faster, because new information displaces old information quickly in your short-term memory. For example, you may find it hard to take in new facts if you’re trying to study while surrounded by conversation in a coffee shop.

Your long-term memory is your background knowledge, or “schema.” Its capacity is much larger and can last for years. Long-term memory helps us contextualize new information and makes it possible for us to build our base of knowledge.

As teachers, it’s our job to help transfer information from the short-term memory to the long-term memory. If we fail to achieve this, all our effort goes to waste.

Three principles

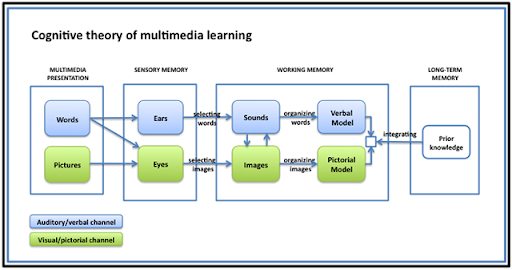

The cognitive theory of multimedia rests on three key concepts.

Dual channel principle. This principle states that we have two main channels for processing new information: the visual-pictorial channel and the auditory-verbal channel. The visual-pictorial channel processes what you see, while the auditory-verbal channel processes spoken language.

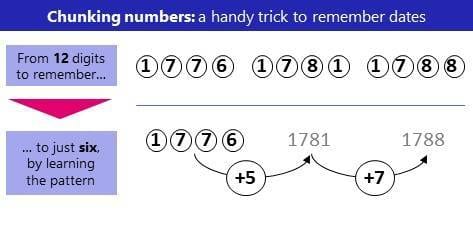

Limited capacity principle. Humans can only take in a small amount of information at a time. Break down information into chunks of 5–7 to help with initial memorization.

Active processing principle. People don’t learn passively. You can’t sit back and listen to a lecture, or read a chapter of a book once, and expect to remember every detail. Instead, students must participate in activities to help consolidate the new information.

Types of cognitive processing

So, if listening and reading alone doesn’t help new information sink in, what kinds of activities do? Students must engage in active cognitive processes to integrate new information into their existing knowledge base. The main techniques used in multimedia instruction for cognitive processing are:

- selecting words and images

- organizing words and images

- integrating verbal and pictorial models.

In summary, students recall information better when they are able to select relevant words and images and organize them into a clear structure. The information should be presented in the context of their existing knowledge. However, the information should be broken up, so students’ short-term memory isn’t overwhelmed.

Multimedia instruction with interactive elements is more effective for carrying new information over into your long-term memory. So how do you leverage this in the classroom?

Effective Multimedia Instruction

Use evidence-based learning strategies

There are a vast array of teaching and learning techniques backed up by decades of research and freely available to read about online. However, teacher training may often miss the most recent scientific findings, as published educational materials can be outdated.

If you are designing a course program, drawing on cognitive psychology is useful: you can refine the focus of your lessons, target students with maximum precision, and consistently deliver a high-quality product.

Key learning strategies you can implement in your classroom today include:

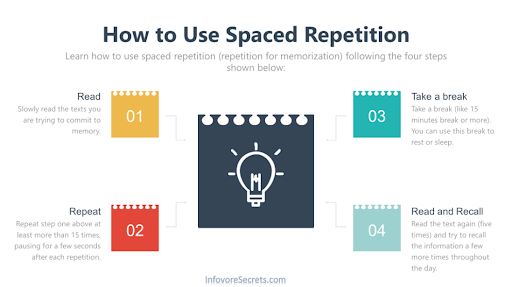

Spaced practice. This means spreading out studying over time. Students must review the contents of lessons, but not immediately afterwards. Instead, they should leave rest time to allow for processing.

This aids memorization. If students are learning a dense subject like MLOps (machine learning operations), they will need to review key concepts regularly to make sure they understand and remember.

When they return to the material, the students should use effective study strategies instead of simply reading their notes again.

Retrieval practice. In other words, memory testing—how well are students able to recall information? Students should put away class materials, and try practice tests or writing down as much as they can without checking their notes.

Elaborative interrogation. Students are encouraged to list the main ideas they need to learn from class materials, and ask themselves questions about how these ideas work. They should then consult the materials and investigate the answers for themselves.

As a teacher, it is critical to recommend supplementary material so that students can do their own research. If you are an online educator, you could collaborate with another platform using one of the many good affiliate packages available.

Interleaving. Interleaving means switching between topics while studying, rather than devoting all of a study session to one topic. Afterwards, students should return and go back over the topics in a different order.

Concrete examples. This means applying concepts learned in the classroom to real life. Humans remember concrete information better than abstract ideas. This is why, when you first learn fractions, you might visualize pieces of pie.

Dual coding. This is how we apply the dual channel principle. Words and visuals must be combined. Students should also be encouraged to draw visuals to accompany their notes, including diagrams, mind maps, or cartoons.

Define outcomes using constructive alignment

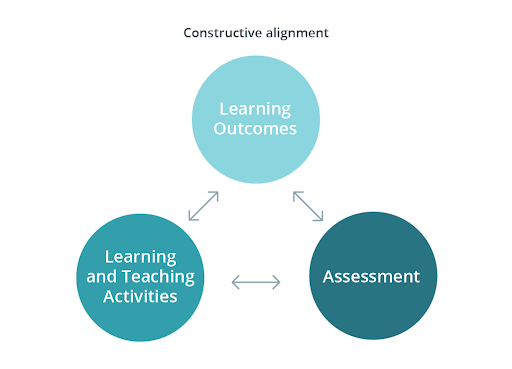

Constructive alignment is a concept originated by Australian educational psychologist Professor John Biggs. Constructive alignment starts with defining the intended learning outcomes (ILOs). This means clarifying exactly what it is we need students to learn. As teachers, we decide the topic of study, but we should also be clear about the degree of understanding we hope to achieve.

Students may attain declarative knowledge (i.e., enough understanding to speak and write about the topic), or functional knowledge (i.e., the ability to put that knowledge to use). This defines the difference between a medical student who can ace a multiple choice test and a fully fledged doctor.

When designing a course, ILOs must include the topics, the depth of knowledge covered, and the functional skills you hope to impart.

The next step is choosing teaching and learning activities (TLAs). These activities must be well-structured, dynamic, and incorporate the use of multimedia. Crucially, they must also have direct relevance to your ILOs.

Finally, teachers must assess students to see if their actual outcomes match their intended ones. Students are likely to do the bulk of their self-study in the run-up to an assessment, so it’s particularly important for the assessment to cover the key learning points in the curriculum.

Overall, using constructive alignment is a simple and efficient way to structure your courses. This concept prioritizes proactive learning and encourages students to take charge of their studies, which additionally helps with cognitive processing.

Multimedia Instruction: The “Do’s” and “Don’ts”

Do use technology

The Internet has changed the way we learn. Generation Z are digital natives. These young learners grew up with the Internet and have never known a world without it. This alters the development of their neural pathways and fundamentally changes their learning needs.

The norm for today’s students is being connected and engaged at all times. Digital natives prefer interactivity and using the Internet to express themselves through blogging or video platforms. They enjoy autonomous learning and independent research. They have an excellent capacity for analysis, task management, and multitasking.

Plus, if you teach remotely, the ability to use technology is an absolute necessity. Whether you’re a traditional teacher working online due to the pandemic, an e-tutor, or even a webinar organizer, mastering hosted business phone systems is crucial.

Allowing students to use e-learning tools is one way to help get them motivated and involved in their learning journey. Self-directed activities such as internet research are a fantastic way to encourage elaborative interrogation.

Most importantly, online learning helps students see their studies as something they undertake themselves with a teacher’s assistance. This challenges the old perception of learning as a passive process that only occurs in a classroom.

Don’t rely solely on rapid e-learning programs

Though technology is a powerful tool, it should be wielded with precision. Activities must be tailored to ILOs.

A common critique of e-learning software is that it prioritizes software design over content. Rather than writing a program around a course, developers will write a course around a program’s features. Applications might be flashy, attractive, and gamified, but there is no educational benefit if all users do is drag and drop multiple-choice questions.

It’s also important to choose software wisely. Clunky, slow-loading applications or glitchy, unintuitive video-calling platforms can create frustration and cause users to disengage. Contact center as a service solutions can help you run webinars and online classrooms smoothly.

Ultimately, make sure students are using a variety of materials for learning, rather than using a single program that may only teach a topic superficially.

Do practice “chunking”

When planning a lesson using ILOs, it’s tempting to be ambitious and try to cover too much of your topic in one sitting. But it’s far more important to remember the limited capacity principle.

Break your lesson into small chunks. If you’re using a PowerPoint presentation, each slide should only contain at maximum one new piece of information. Any pages you publish online should follow the principles of SEO (search engine optimization): simple, clear, with plenty of videos and imagery.

Don’t include unnecessary detail

As teachers, we all experience the urge to give students a rich, immersive experience. But for newcomers to any given subject, this is far too overwhelming. People remember information better when it’s boiled down to the essentials. Even graphics, music, or fun trivia can bog down your lesson unnecessarily.

Do use animation

Animation is a simple, colorful, and fun way to illustrate the content of your lesson. Interestingly, animation is also often used in marketing and when creating a website video pop-up as it catches attention and engages viewers. Tricky concepts can be made clear using concrete examples illustrated through moving images. When the animation is combined with a spoken voiceover, the dual channel principle can be utilized for maximum impact.

Don’t use animation and written text simultaneously

Animation and text both use the same channel: the visual channel. Forcing students to read written text and follow moving images at the same time risks cognitive overload. They’re unlikely to be able to remember the lesson’s content if they’re struggling to look at two different things at once.

Do present the same information in a variety of ways

Not all students will have the exact same learning styles. Some will respond better to video content, while others might prefer reading and note-taking. Plus, viewing the information again in a different way after a rest period helps with spaced practice, keeping the memory fresh.

Do keep it chatty

Humans learn more quickly when they are motivated by social cues. This is why it’s easier to become fluent in a language if you already live in the country, and why customers prefer a real customer support agent to a plain FAQ page. If a student feels that their teacher is a social partner, consciously or not, they will find it easier to remember what they say.

Thus, teachers should use informal, conversational language while teaching. Examples could be given in first or second person (e.g., “Imagine you’re at the supermarket…”), instead of the third person.

When using multimedia elements, video clips should wherever possible include a speaker talking directly to the camera, using a natural conversational style and gestures. Research shows that students learn better from any humanlike figure, even an animation.

Summing Up

Learning involves a complex series of processes. It’s never as straightforward as reading a textbook, listening to a lecture, or taking one exam. As a teacher, your job isn’t about transferring information from your mind to your students; it’s about empowering them to take charge of their own education.

Take cognitive psychology into account and define clear learning outcomes. Be selective when choosing digital tools such as an e-learning application or a VoIP provider. Combine a variety of effective and memorable multimedia classroom materials, and your students will never be bored again!

See also: